Is agritech the next big thing?

Smallholder farming, food systems, and the promise of digital agriculture

There are more than 510 million smallholder farms in the world producing some $2tn worth of food annually.1

Despite their importance in global food systems – representing 84% of all farm holdings and producing one third of all food2 – they face undue economic marginalisation and hardship.

Most smallholder farms live in poverty, insecurity, and constant need of complementing their insufficient income with off-farm streams. They also face a succession planning issue – the smallholder farmer population is aging while younger generations opt out to pursue other more prosperous occupations elsewhere, often in cities.

Farmer pain points

Two chief reasons for smallholders’ current state of affairs are market exclusion and low competitiveness. Their scale and fragmentation pose a challenge for them to access end markets for their produce which limits their agency and bargaining power. And their resource poverty leaves them unable to invest in quality inputs thereby making it difficult to compete with larger, more industrial farms.

Agro-cooperatives, which exist to alleviate such pains, are limited in reach, scope, tech intensity, and success – especially in regions with a high concentration of smallholder farming.

Beyond agro-specific challenges, smallholders are also the most vulnerable cohort to economic (e.g. COVID-19 supply chain disruptions) and climate-related (e.g. extreme weather events) shocks and stresses – events that are happening with more frequency and pose a threat to their livelihoods.

Wide lens view

In spite of this, there is a broader social, economic, as well as environmental need for a livelier smallholder farm existence.

To cope with growing demand, food systems will need to deliver 50% more food by 2050.3 The FAO estimates that, with current resource constraints, the majority of this increase will come from yield enhancement – an opportunity which exists predominantly within the smallholder farm domain.

The resilience of food systems is also a topic of increasing concern, particularly in the wake of COVID-19 disruption. The increased diversity and quantity of food source nodes, as well as of food trade flows, are characteristics of a more resilient system4 – ones which can only be achieved by better integrating smallholders into the global food supply chain.

Large-scale, intensive mono-cropping is degrading the quality and sustainability of our natural environment,3 which poses a threat to life on Earth. Smallholder farm success is one of several elements that are key to maintaining biodiversity and the sustainability of agricultural systems.

Technology in farming

The plight of smallholder farms is unjustifiable in this day, where tech has the capacity to level the playing field as well as make the occupation “sexy again” for a new tech-savvy generation of farmer.

For any VC who’s quick on the uptake, this confluence of micro and macro-level need on a wide-scale presents an opportunity to partner up with the right founders on unique and exciting journeys. While some interesting agritechs have popped up in different regions of the world – e.g. Kenya, Ghana, Egypt, Turkey, Pakistan, India, Korea, China, and USA – there is yet a lot of ground to cover in this space.

So how exactly can tech enable smallholders to thrive?

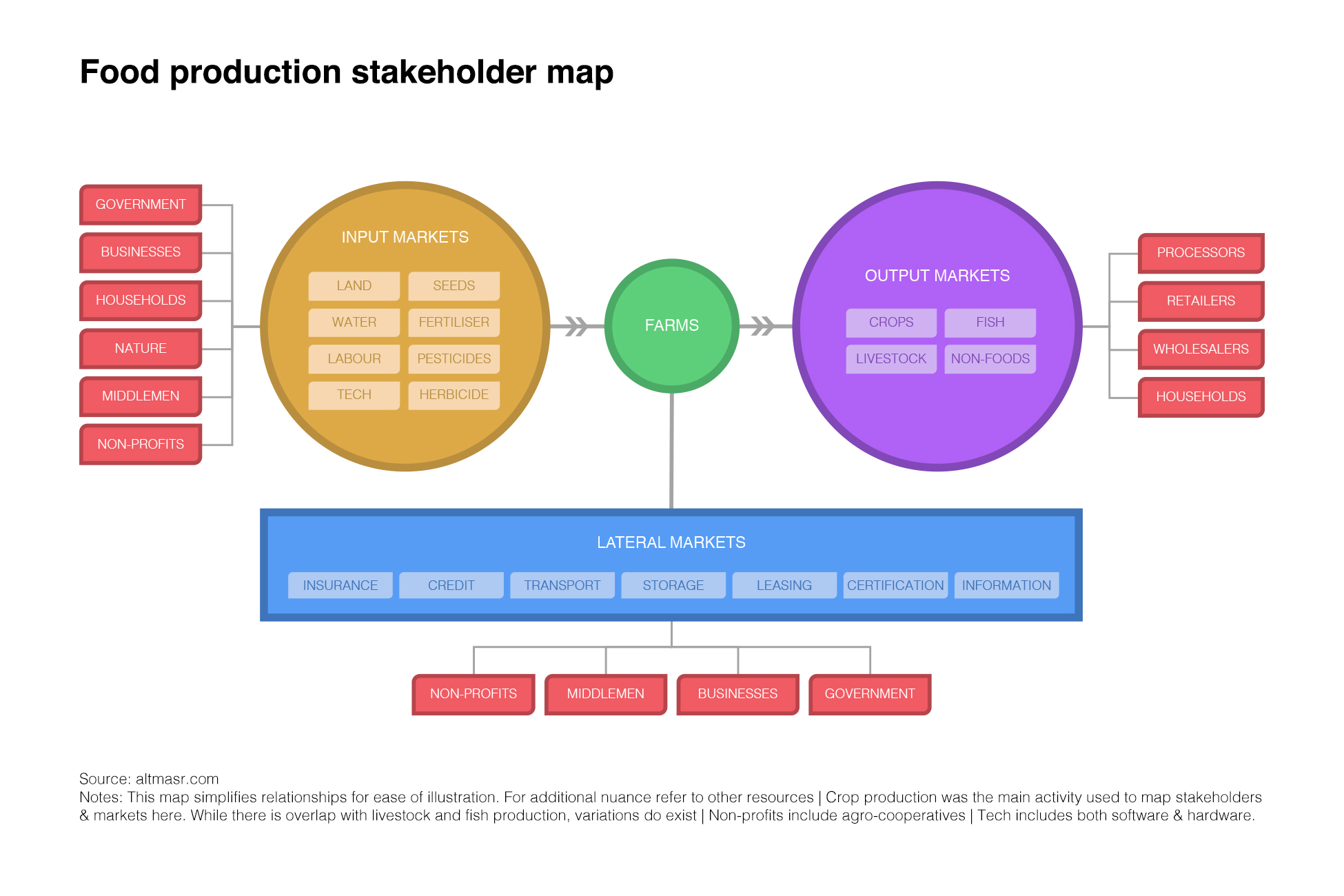

Markets

Bridging the gap between smallholder farms and end markets – where food retailers, processors, and consumers are buyers – is “ground zero” for empowering them.

Between them is a long chain of low-value-add middlemen, that buy and pool produce and engage in varying levels of wholesale commerce. In the absence of alternatives, farmers may depend on them for supply of inputs, credit, and harvest labour, as well as in crop selection. They are often powerful chain actors and command a high share of the margin stack.

Facilitating digital marketplaces for farmers and end market off-takers to transact directly is of considerable value to both chain actors. The value is in the ability to enter into forward contracts for the future delivery of produce – spot markets are only of marginal benefit in this case. Farmers enjoy more agency, visibility, security, and better pricing, while off-takers are able to tap into new supply nodes.

Digital marketplaces for agricultural inputs are also powerful enablers. Food safety requirements and contract specs place constraints on farmers in terms of inputs they can use – seeds, fertiliser, pesticide, herbicide, etc. Facilitating market access, product availability, guarantee of product authenticity, logistics, and price transparency, makes it easier for smallholders to do business in higher-value markets.

Fintech

There are 4 main financial products in which tech becomes meaningful for smallholder farms – credit, payments, insurance, and wallets.

Credit is a major concern for farmers given inherent working capital requirements and relatively long operating cycles, especially for smallholders who often have limited resources at their disposal.

The ability to accept digital payments is key to success, particularly when engaged in microcontract farming with large enterprises. This is a challenge for unbanked smallholders.

Ownership of a digital wallet/account allows unbanked farmers to receive and store inbound credit and revenue, as well as make digital payments for inputs.

Capital commitments, agricultural risk exposure, and limited disposable assets dictate smallholders’ critical need for adequate insurance cover, e.g. crop and livestock insurance.

Availing to smallholders access to such products – either as standalone fintech solutions or embedded within other marketplaces/platforms – bolsters their agency and ease of doing business in sophisticated end markets. The use of data to offer optimised credit pricing and insurance premiums are potential differentiators.

Precision agriculture

Low yields are characteristic of smallholder farms. A core contributor is their limited investment in technology – something that’s become mainstream in large-scale agribusiness.

Remote sensing via satellites, drones, or IoT devices is increasingly being used to monitor variables like soil health, crop health, temperature, humidity, crop growth, as well as to plan spatial crop structure. The data collected is powerful in enhancing farmers’ decision making, resource allocation, yields, and in turn their profitability.

Farm management SaaS allows smallholders to leverage that power in running their operation while avoiding hefty capex. This helps bridge the gap in their competitiveness vis-à-vis larger farms.

Supply chain

It is typical for agribusinesses to be vertically integrated. This gives them control over various nodes in the supply chain – e.g. post-harvest handling, storage, and transport – which is useful for minimising food loss as well as complying with food safety requirements of large and international markets.

The capex associated with that is beyond the means of smallholders – leaving them to deal with middlemen and/or informal service providers – which can cripple the competitiveness of their product and their bargaining power.

Traceability is also a key consideration in modern food systems – born out of increased food safety regulation and the heightened risk of hazard. This is basically the need to be able to trace a batch of produce back to its origin, and identify where it was grown, the inputs used, and the supply chain nodes that it’s passed through.

To comply, large agribusinesses either invest in traceability infrastructure or contract the services of expensive legacy providers – again to the exclusion of smallholders.

There are opportunities to commodify traceable and reliable post-harvest services (e.g. storage and transport) for smallholders, in the same vein as digital trucking, mobility, or fulfilment platforms. The blockchain is a resource for next-gen traceability.

This enables farmers to easily plug into higher-value markets, access previously out-of-reach ones, relieve themselves of post-harvest burden, and focus on maximising the success of their farm.

Social networks

Agricultural extension is the process through which farmers update their knowledge and practices in ways that help them be better and more successful at what they do. This can take place as farmer-to-farmer advice or through dialogue between farms and specialised organisations – often ones that help channel new information from the scientific community to the farming one.

The role of such networks is becoming more potent particularly in light of new knowledge about the interplay between agricultural systems and our natural environment, and the role of sound land, water, and soil management practices in preserving the integrity of both – practices that ultimately affect farmers’ livelihoods.

Digitising and formalising these networks/communities has the potential to maximise their reach, participation, and impact – think Stack Overflow for farmers.

Agritech platforms

Of the digital solutions mentioned, it is synergistic to bundle them together as part of multifaceted agritech platforms – or “super-apps”. There is precedent for various successful combinations. And their scope is not limited to only smallholders – there’s evidence to the potential of spill-over adoption amongst medium-sized farms as well.

Regional opportunity

So where is the opportunity most immediate?

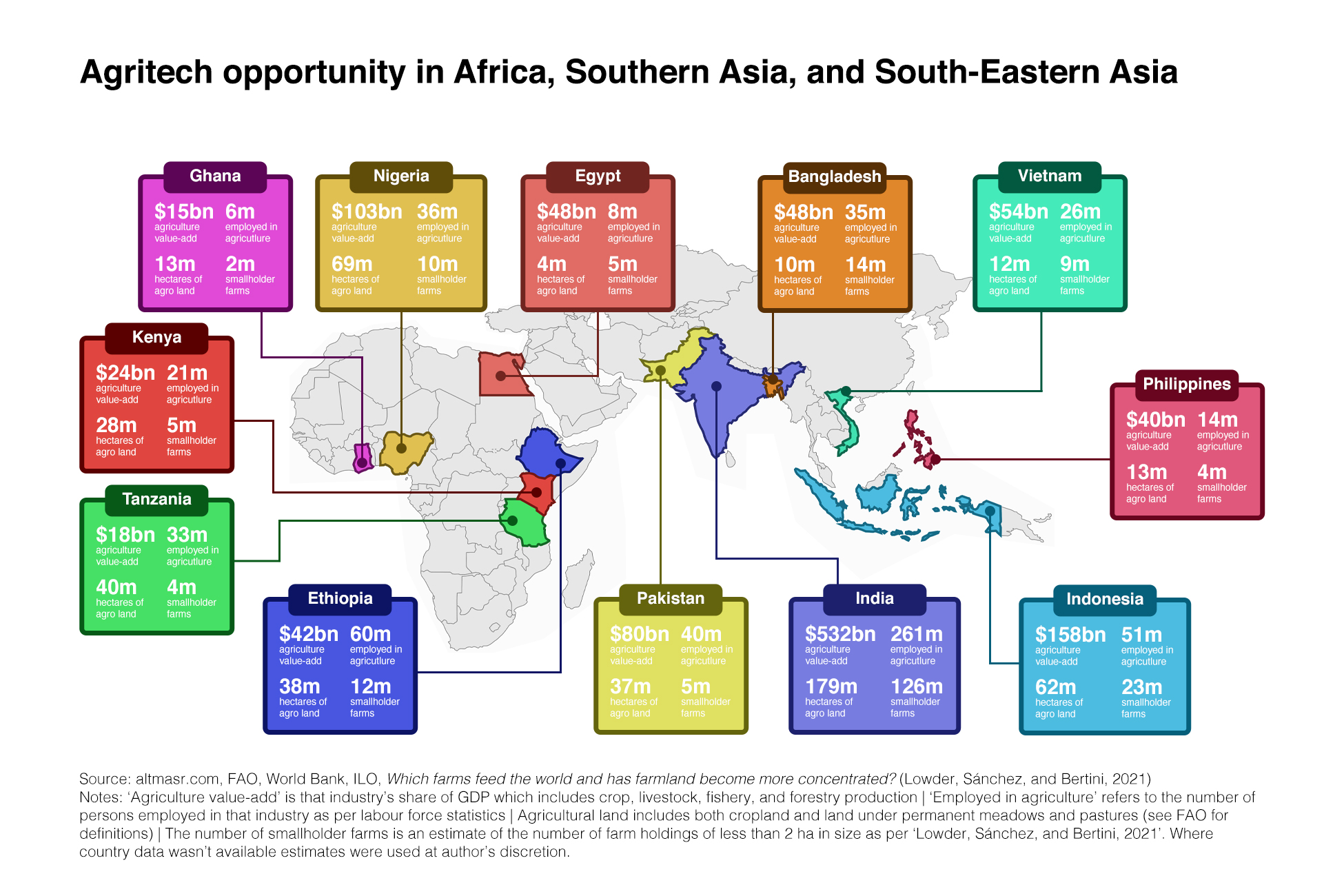

There are 3 regions that stand out for having large numbers of smallholder farms contributing a sizeable share of food output and with ample potential for tech disruption. Those are Africa, Southern Asia, and South-Eastern Asia.

Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania are standouts in Africa. While Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines, and Vietnam are ones in Asia.

Risk considerations

Agritech is a vertical where it makes sense to back founders with a deep understanding of farmers’ struggles – typically ones with domain expertise. The stakeholder landscape is complex, with a lot of moving parts, and it’s not easy for outsiders to crack.

Regional infrastructure, economics, and demographics also have bearing on product success. Internet coverage in rural areas, broadband speed, broadband cost, smartphone penetration amongst farmers, as well as their digital literacy pose challenges for adoption. The latter two relate to an ageing population – generational succession will take time.

Stakeholder collaboration and/or tech-based workarounds for these challenges – e.g. satellite broadband access, low cost smartphones with payment plans, low data intensity product design, user education programmes – are things to consider.

Final thoughts

Changing the status quo in this space is tough – more so than most other verticals. Yet the size of the problem and its potential impact make it an attractive one to take on.

Watch this space closely – it’s on track to become big in the next decade.

-

Smallholder farms are those that are less than 2 hectares in size. (2 ha = 5 acres = 5 feddans) ↩

-

Lowder, S., Sánchez, M. and Bertini, R., 2021. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated?. World Development. Online here. ↩

-

FAO. 2022. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture – Systems at breaking point. Main report. Rome. Online here. ↩↩

-

FAO. 2021. The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. Making agrifood systems more resilient to shocks and stresses. Rome, FAO. Online here. ↩

#tech #startups #entrepreneurship #agritech #food #supply_chain