Is edtech the way forward for Egypt?

How human capital challenges have been a drag on Egypt's economy and how tech in education can help break the cycle

Human capital has become an indispensable asset for countries today. The cross-border movement of goods and services that comes with globalisation pits the domestic output of economies constantly against that of foreign countries. To compete with the diversity and complex production of the most advanced economies, countries must maintain high levels of productivity and innovation. This goes hand in hand with having a skilled, knowledgeable, and technologically literate workforce. How well countries can maintain that dictates the level of income that residents can generate and, in turn, their standard of living.

Countries recognise this and invest in their people’s education. It is among the top priorities for governments worldwide. On average 14% of public spending goes toward education1, with the aim of making it universally accessible to citizens and attracting top talent to teaching professions. It is typical for countries to require by law that citizens attain education up to a certain level within formal education systems (up to age 18 in Egypt). This is largely to ensure their young population are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for them to be able to assert their ambition and realise their potential as productive members of society.

In spite of that, nations’ education outcomes vary in success. Egypt is a good example where they've fallen short of aspirations. The country ranks amongst the bottom third of 141 countries based on the skill level of their workforce and efficacy of their education systems.2 This deficit manifests itself in the economy in a multitude of ways, but most tellingly in the low levels of productivity and the low-level of complexity in the goods and services produced. Per capita GDP3, commonly used as a yardstick of productivity, is 26% lower than the world average and almost 5 times as small as that of the top 10 countries ranked by skill.42 In terms of the relative knowledge intensity of economies, and consequent complexity of their output, Egypt ranks amongst the bottom half of 127 countries surveyed.5

Education and teachers in Egypt

The reasons for this become clear when one considers the fact that the overwhelming majority of students in the country are excluded from access to top quality educators6. Research has shown that teacher quality is the strongest predictor of the quality of education.78 Public schools cannot afford to hire them and private schools, with their traditional cost structure, would have to charge high fees to be able to attract them – fees that are way beyond what is affordable for most households.

Similar to the ratio in countries with the most developed human capital, around 90% of students in Egypt attend public schools910. However, public spending on schools per student in Egypt is one-thirteenth of what it is amongst the top 10 countries ranked by skill.3102 This is not by design – an overstretched state budget simply can’t afford more than that. Given that about one-half to two-thirds of this spending goes to fund teaching-staff compensation,10 this order of magnitude difference is an indicator of the disparity between the standard of living commanded by public school educators in Egypt and other countries with skilled workforces. Compared to other professions nationally, being a public school educator in Egypt places you somewhere within the bottom quarter on the income scale.1112 With such economics, public school careers are hardly well placed to attract the most ambitious talent.

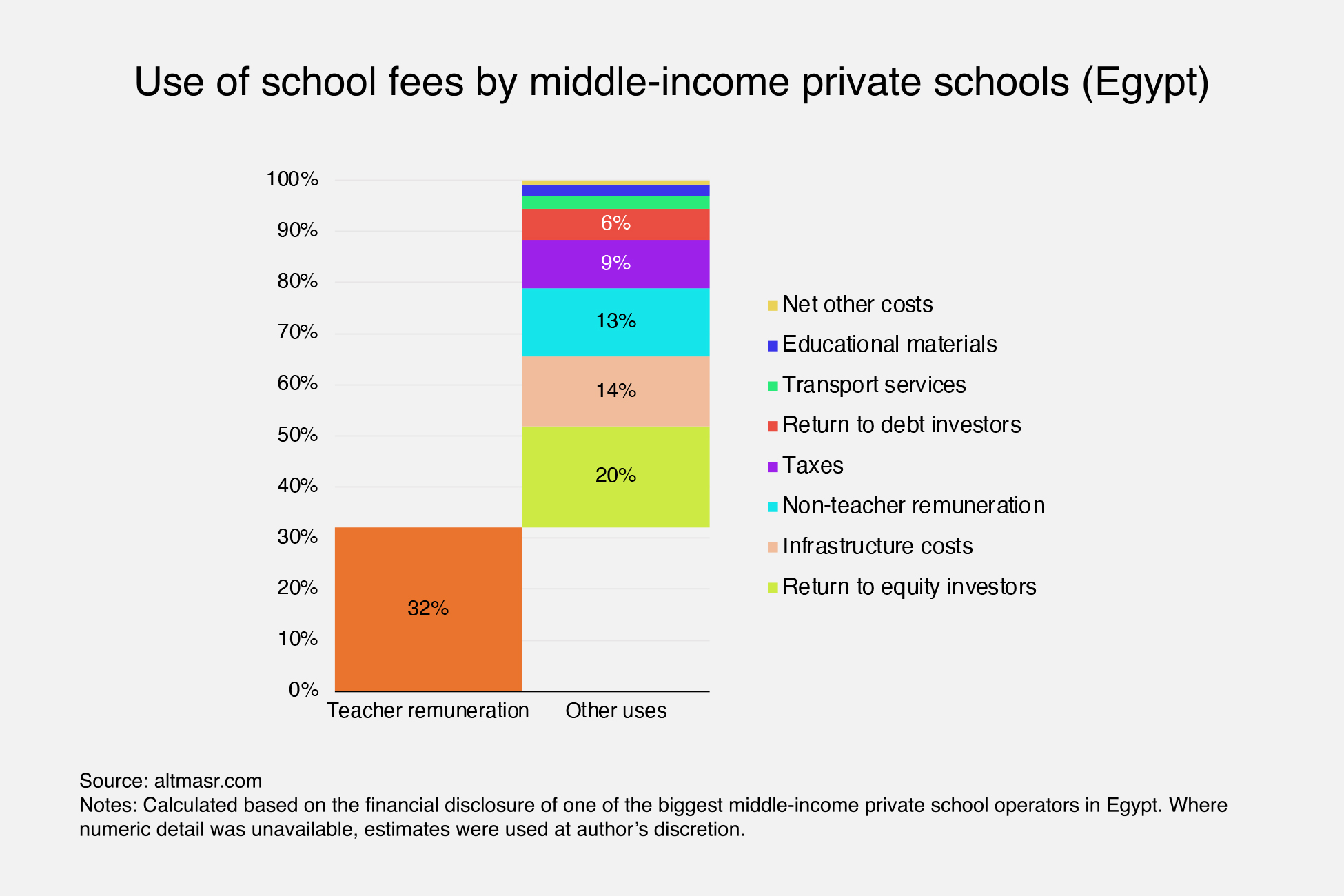

Private schools are not generally much different. Using public data from one of the biggest private school operators in Egypt that caters to middle-income households,13 teacher remuneration is found to not be much more attractive on average than at public schools despite the higher school fees. On analysis, only around a third of the aggregate school fees paid are used to compensate teachers, with the lion’s share of the balance accruing to buildings and infrastructure-related costs, remuneration of non-teaching staff, taxes, and compensating investors for the capital they’ve put up. For the same schools, with the same quality of facilities and resources, to use competitive compensation to attract good teachers, it's estimated they would have to raise their prices on average by at least a factor of 3. Such school fees would be out of reach for an overwhelming majority of the population.

Need for change

So how did Egypt reach this point, where a good education can’t be afforded by the state nor most households and the economy is in bad shape for it? This is more likely than not the result of a vicious cycle in which Egypt has been trapped for several generations. It takes only one generation of administrative neglect throughout which students receive substandard education to eventually bring down the relative competitiveness of an economy versus others, particularly those which have done better at training and skill building. In a globalised world, this likely results in less income accruing to domestic households in favour of foreign ones. In the absence of any counter measures, the lesser quality output of such an economy ultimately provides education inputs for the next generation – e.g. knowledge, culture, skills, curriculums, policy, pedagogy, etc. With a fast growing population like Egypt’s and rapid globalisation, such a problem snowballs with every turn of the cycle making it that much harder to break.

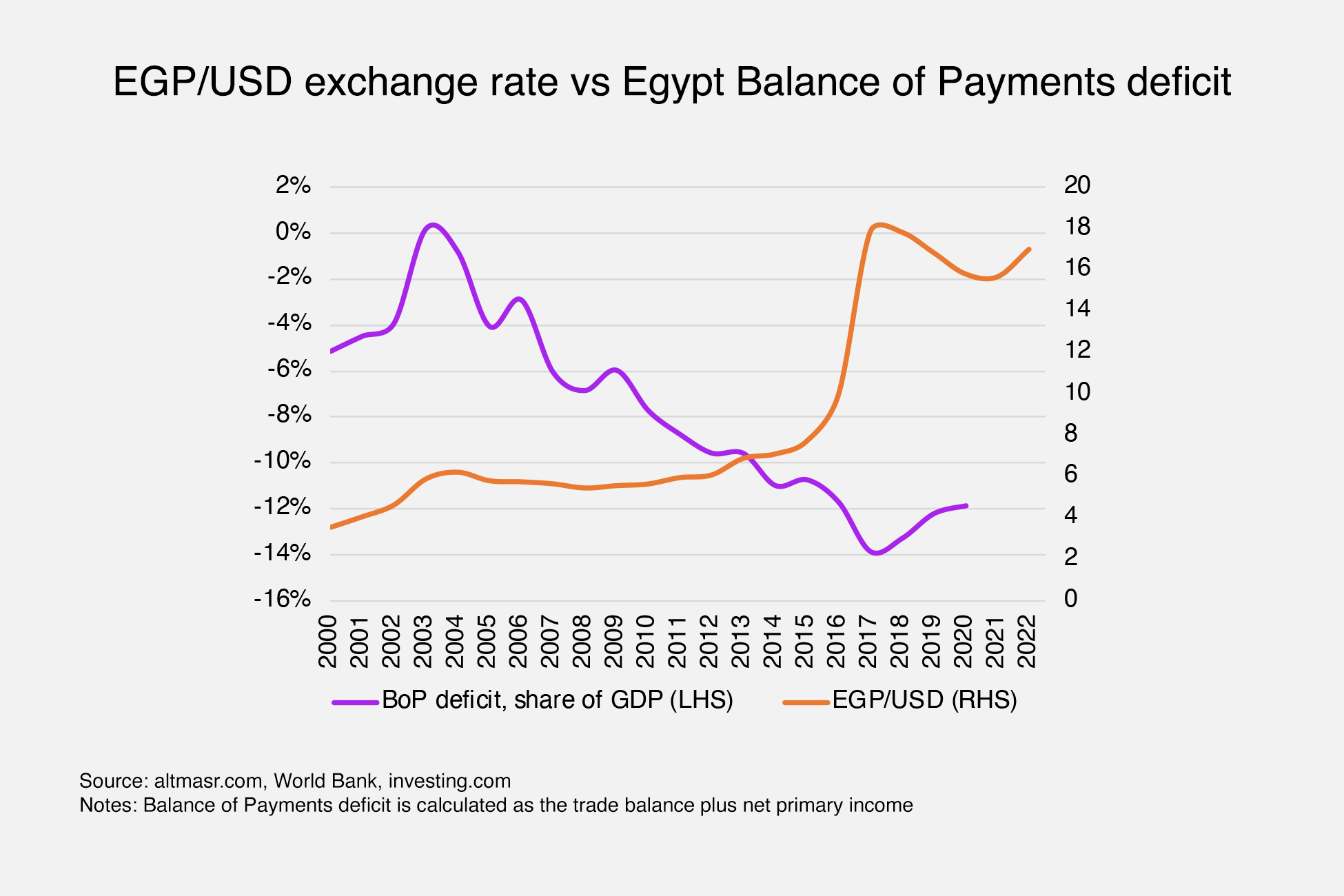

Why is this critical to address now? The economy is worsening and unless measures are taken to improve human capital the situation is unlikely to get any better. The adverse combination of low productivity and relative uncompetitiveness has put Egypt’s Balance of Payments (or BoP) in a state of ‘imbalance’. Despite sizeable inflows from tourism and Suez Canal receipts, Egypt ranks in the top third of 166 countries by the size of their BoP deficit14 as a share of GDP. Put simply, the country imports a large portion of goods and services and doesn’t generate enough income on aggregate to pay for them. Typically the shortfall is plugged by a combination of inbound remittances from nationals working abroad, foreign investment (recently volatile short-term debt), and grants.15 This precarious set up, coupled with the fact that the imbalance has been chronic, growing, and not met with sufficient gains in domestic productivity, is the reason behind the Egyptian pound losing more than three quarters of its value in the last two decades16. Recent developments place this issue in even sharper relief.

Another reason to address this sooner rather than later is the fact that the average household has limited freedom of choice when it comes to procuring education for their children – they are generally unable to maximise education quality per pound spent. They can choose between sending their kids to public schools at little to no cost but receive a subpar education, or spending a sizeable share of their limited income on private schools and receive in most cases only a marginally better product. This situation is made even graver when considering the unfavourable market dynamics at play. Demand for K12 education is understandably inelastic. This fact coupled with the fast pace of population growth is straining capacity on the supply side of the market. There is currently a shortage of at least 20,000 classrooms per year.41012 In the absence of a fiscally healthy state with a strong handle on education, a naturally opportunistic private sector is plugging the investment gap. Yet the combination of inelastic demand with chronic supply shortages (not to mention high barriers to entry) gives obscene bargaining power to school shareholders vis-à-vis households and educators. There is built-in upwards pressure on school fees as well as downward pressure on teacher’s salaries. Meanwhile there are few to no competitive pressures on private schools to deliver a best-in-class offering with the resources at hand – as long as they can deliver the minimum level of education required by domestic labour markets (no matter how poor by global and cultural standards) they will remain in business.

Food for policy

So what needs to happen in the immediate term to improve education outcomes at the national level with the given level of resources?

It’s important to conceptually decouple education from infrastructure. Egypt has one of the highest costs of capital globally. This means that for each unit of capital spent on school infrastructure, investors require more compensation for it than in most other countries. If anything this underlines the distinctiveness of economic levers in Egypt versus other countries, and hence the inefficacy of one-size-fits-all education policy – a more bespoke solution is needed. Building new schools needs capital for acquiring land, buildings, buses, desks, chairs, and equipment. We estimate that, of aggregate private school fees paid by households, at least 26% accrues to cost of capital (both equity and debt) and around 14% are used to cover infrastructure related expenses (e.g. depreciation, maintenance, and utilities). That’s at minimum 40% of expenditure by households that is potentially not being used to facilitate higher quality learning.

Schools are also ripe targets for disintermediation. They siphon a lot of value from national expenditure on education and what’s given back is not adequate. Take the teachers out of schools today, and their role is approximate to a combined registrar and day-care centre – they register students for exams and qualifications on behalf of third parties, and they watch over children and keep them occupied while parents hold their day jobs. These are necessary roles to fulfil, but can be done at a fraction of the cost of what schools effectively charge for.

The most important change that needs to happen is that teaching generally needs to be made more attractive as a career option for ambitious professionals. As custodians of the future prospect of the economy and its labour force, it is a critical occupation and it needs to be in better shape. Teachers ought to be empowered – they should enjoy more agency, more potential for economic mobility, and an expanded ability to reap the rewards of meritocracy. This is put in sharper focus when considering the current density of classrooms and chronic excess demand for education – there is a growing need for more teachers.

Technology and neo-schooling

How can these ideas be applied in the real world? With the use of technology and a new business model. A changed demography and economy, as well as the availability of new technology, has made obvious the fact that Egyptians’ need for education has evolved beyond the traditional school framework. Instead of dedicating expensive resources to schools, education can make use of underutilised existing ones. And instead of being school employees, teachers ought to be exchanging value with households directly, within the framework of an enabling ecosystem. It is easy to infer how this would yield better economics and improved education outcomes.

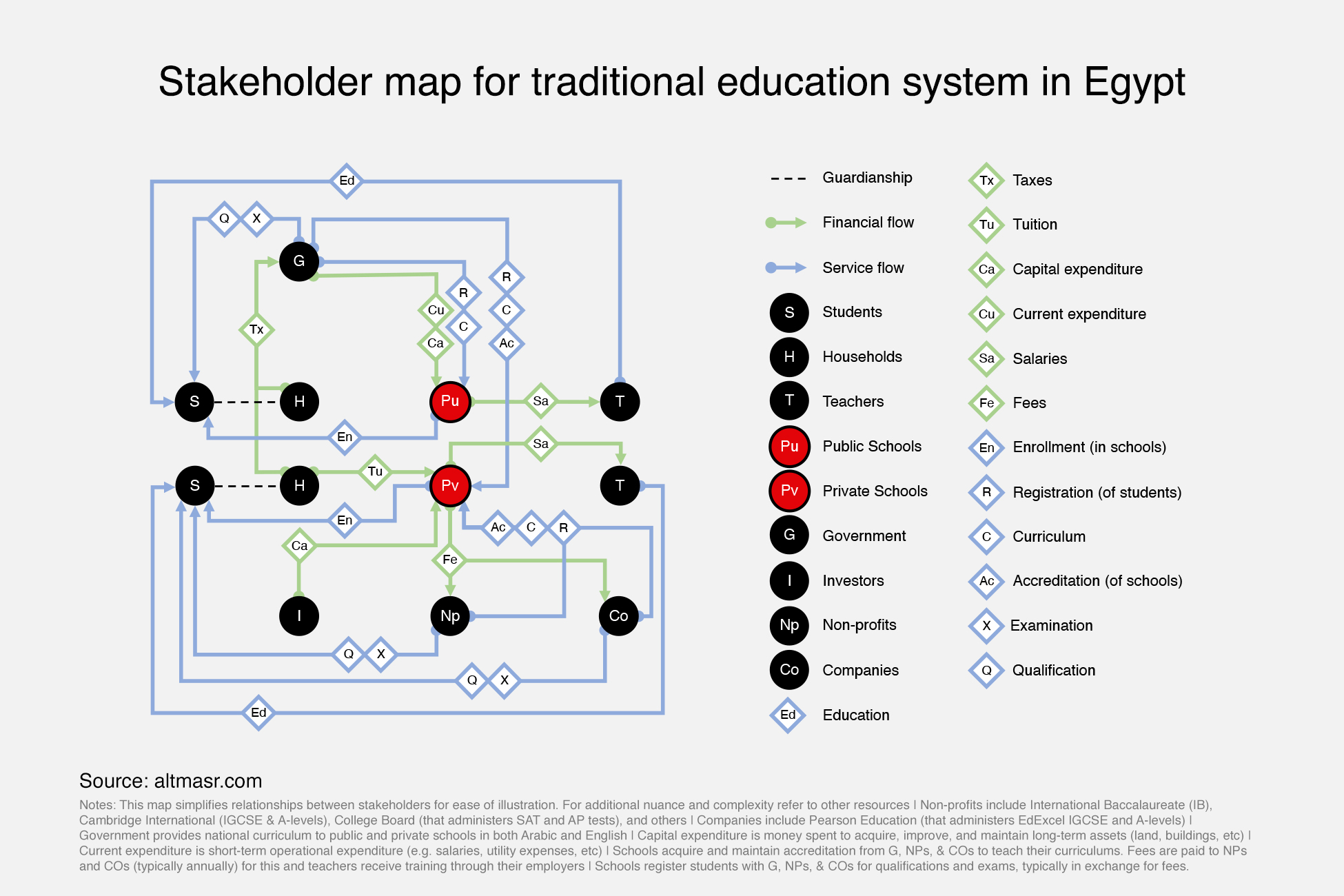

Consider the way stakeholders interact within the incumbent education system. Qualifications are generally awarded by the state, international non-profits, or companies.17 Qualification-awarding institutions (QAIs as they will be called here) typically also function as examination boards – they set exams, administer them, mark them, and distribute results. To sit for exams and be studying towards earning a qualification, students need to be registered with QAIs. Registration is typically done by schools on behalf of students. For schools to include a qualification amongst their offered programmes they first need to be accredited. Non-state accreditation is typically a process that involves a combination of applications, assessments, inspections, and the payment of fees. As part of a school’s accreditation process, training is typically provided to teachers employed by them – they are made familiar with the particular curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment methods. Fees are paid by schools towards non-state QAIs not just for the process of accreditation, but also for maintaining it, registering students, administrating exams, marking exams, sending out results, and the right to use branding. Fees generally recur either annually or by instance of service. The costs paid to QAIs naturally inflate the price of education at schools that offer non-state qualifications versus ones that don’t. For households, the education their children receive is a function of the school they’re enrolled in, the qualification they’re studying for, and most importantly the teachers hired by the school.

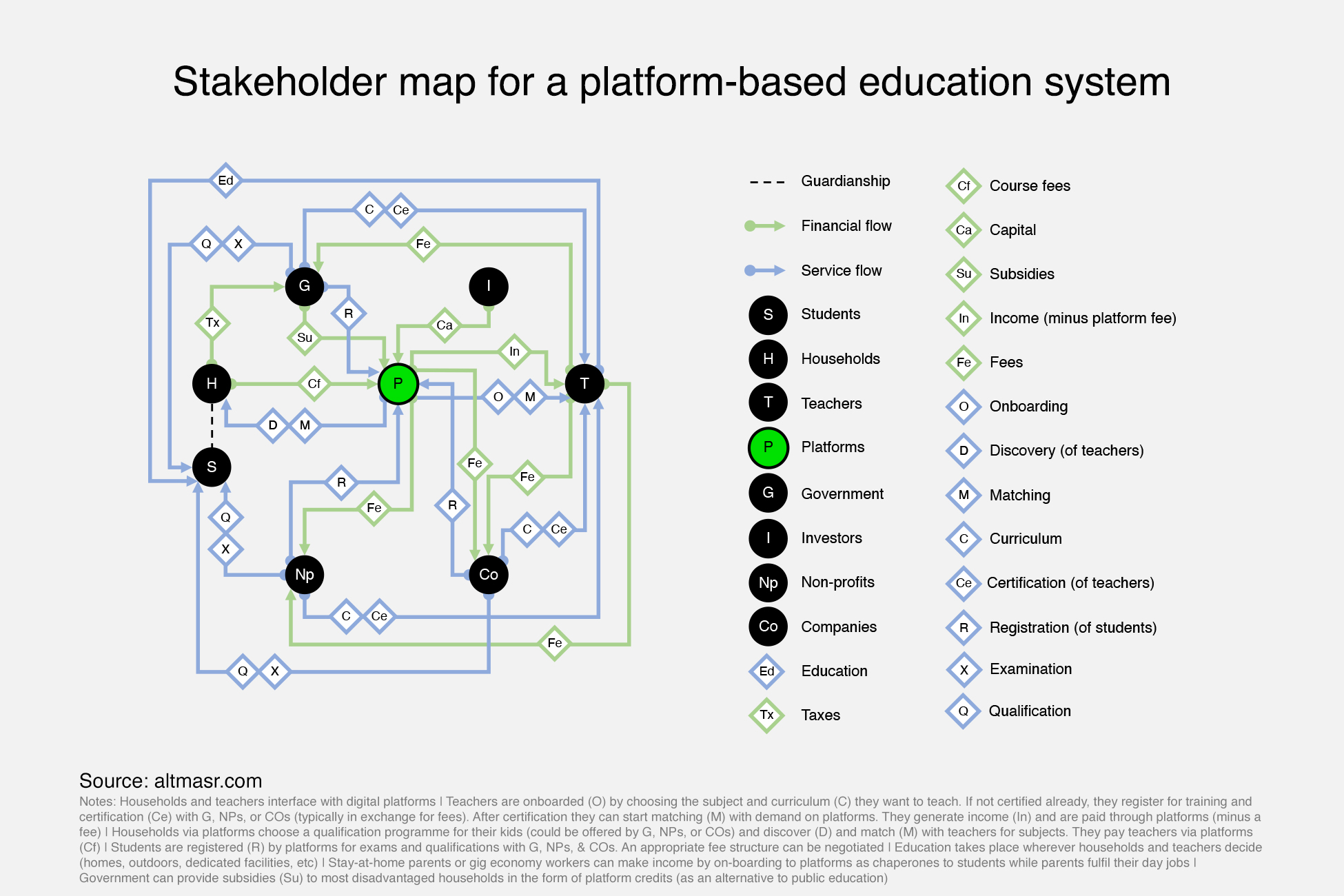

Replacing schools with digital platforms has the potential to streamline value exchange and maximise access to quality educators.

The business model of QAIs would need to change to serve beneficiary stakeholders directly. Accreditation of schools ought to become certification of teachers. And registration of students for exams and qualifications can be done digitally at the behest of households.

Digital marketplaces can match household demand for qualifications and education with supply of teachers. Many equilibriums can be found for pupil-teacher densities, teacher work hours, and course prices depending on the locale, demand for qualifications, household spending power, and teachers’ individual preferences. Scaling capacity to meet new demand would be as easy as new teachers onboarding to platforms.18 Households can also flexibly tailor aspects of their children’s education to their preference – if language ability is more important to them (as is the case in Egypt generally for English proficiency) they can spend more on higher quality language teachers without affecting the rest of their consumption mix. Quality control can be managed by the marketplace via ratings, reviews, and track records.

Non-curriculum education can also come into play here. Households that are willing and able can add off-programme subjects to their consumption mix as they see fit – subjects like financial literacy, hospitality ethics, sex education, and civics to name some examples. On the teachers’ side, this would expand market opportunities and create new jobs.

Under this model education would be real-estate-agnostic – it can take place anywhere. Households and teachers can agree on “classes” taking place in homes, outdoors, or dedicated learning facilities. Even if facilities were outsourced to third parties, better utilisation rates would improve cost economics. Scheduling would naturally be more flexible and is a component that would need to be managed well by platforms. Stay-at-home parents or gig economy workers can make incomes as chaperones for students while parents fulfil day jobs. At exam times, students can convene wherever QAIs administer them and sit for their tests. Results can be accessed directly by parents through digital platforms.

Evidence to the potential of communities to adopt a more decentralised “schooling” model, however limited, can be inferred from the rise of learning pods and micro-schools during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to note that the fluency of technology would be key in attaining improved economics and learning outcomes. A platform business with low tech intensity would very likely devolve into yet another cost-bloated middleman. Only if platform software is efficient at automating most of what schools stood for would more value accrue to teachers from education spending. Traditional school-related expenditure for non-teaching staff, infrastructure, as well as costs of capital can be greatly reduced. Revisiting the example of middle-income private education, an estimated 45% of expenditure by households can be saved or spent on better teachers. If taxes on education were lifted19, the estimate would be more than 50%.

Stakeholder involvement

Three key stakeholders have a role to play in this scenario. Entrepreneurs need to create digital platforms that facilitate this new model of education, QAIs need to adapt, and the government needs to create a legal and regulatory environment that helps such platforms flourish. The government also needs to keep an eye on monopoly formation, as digital platforms naturally lend themselves to that. There must always be competition between at least two platforms to ensure the welfare of households and teachers is upheld. Given the critical nature of education to a nation, it would not be unreasonable for the government to attempt to create such a digital platform and offer it as a public utility. However, the execution track record of the public sector does not make this an encouraging idea. As an alternative to public education, the government can give subsidies to the most vulnerable households in the form of platform credits.

The government would also have a vital role to play beyond the scope of digital platforms (but in spite of them). They’d need to meet the increased adoption of decentralised schooling with commensurate investment in public facilities for sports, culture, and recreation. The logic is that students would still need outlets to express their physical and artistic selves in the absence of the school playground, art rooms, and theatres. The same goes for public libraries. This is particularly vital when considering the aggregate shortage of such public facilities in Egypt. It is worth noting that execution needs to happen with both universal access and good design in mind.

Final thoughts

It is important to consider the ideas expressed here in conjunction with other facts. The word education here refers to primary and secondary varieties (or K12). Their place as “ground zero” in a typical adult’s educational journey makes it necessary to examine them first in the context of poor education outcomes nationally. Tertiary (university-level) and technical education stages are worth at least equal scrutiny in that regard.

It is key to consider not just the question of who is teaching but also what is being taught. Curriculum content must maintain relevance and usefulness in the context of changing economics, science, technology, and culture. The dominance of software in business and hence the utility of software development skills is a good example of such change.

Needless to say, human capital is only part of the story. An educated workforce can’t be effectively mobilised without the presence of an enabling environment. This includes the rule of law, a fair system of resource allocation, and strong public policy. Such an environment is necessary to also avoid human capital flight.20

The intention here is not to provide an ideal imagining of schools nor to reinvent educational paradigms. But rather redraw the system through which education value flows in such a way that would improve the Egyptian status quo (and that of any countries with similar economics). There have been efforts by the state to do so but not radical enough. The same can be said of the current cohort of domestic tech start-ups – they are trying to create value within the broader education market,21 yet schools remain largely undisrupted. It is critical for change to happen to preserve and promote the welfare of the domestic economy, particularly given the low skill levels and the chronic net flow of value out of the country. The ideas presented here are done so in the hope that they'll help in bringing that change about.

-

World Economic Forum – How to End a Decade of Lost Productivity Growth. Available online here. ↩↩↩

-

Measured in PPP to adjust for differences in the cost of living. ↩↩

-

Motivated and ambitious persons with a talent for education who have chosen teaching as their full-time profession. ↩

-

Our World in Data – Quality of Education. Available online here. ↩

-

Our World in Data – Financing Education. Available online here. ↩

-

"Schools" throughout the article refers to primary and secondary education (or K12). ↩

-

Calculated using data from UNESCO Institute of Statistics. ↩↩↩↩

-

Company is publicly-traded on the EGX. Financial statements are available online. Where numeric detail was unavailable, estimates were used at author's discretion. ↩

-

Defined as the trade balance plus net primary income. Negative sums represent deficits and vice versa for surpluses. Ranked in descending order from biggest deficit to biggest surplus. Data from the World Bank. ↩

-

Qualifications by the state include Thanaweya Amma. Examples of those by international non-profits include IGCSEs and A-levels by CAIE, International Baccalaureat by IB, SATs and APs by College Board, and the French Baccalaureat (administered by a non-profit department of the French Government). Those by companies include EdExcel IGCSEs and A-levels by Pearson. ↩

-

After applying for and receiving certification from QAIs. Such processes should be easy to access by prospective teachers but be rigorous enough for quality assurance purposes. ↩

-

Taxes should not be levied on education in Egypt. Households already pay taxes and are forced to spend out-of-pocket on education in private markets due to the poor product offered by the state. Taxing it in this case, especially given that households rather than businesses bear the cost, is effectively double-taxation. ↩

-

An abundance of high quality opportunities and the right enabling environment are necessary to attract human capital to stay or come. The burden of enablement falls on the state, and that of opportunity on the education system – it needs to produce enough high skilled workers that will create new jobs and/or level up the standard in the job market. ↩

-

Examples of that include digitising markets for academic support (e.g. private tutoring), introducing virtual classrooms, expanding markets for autonomous education, and increasing access to informal learning resources. ↩

#edtech #egypt #education #tech #schools #teachers #human_capital #startups #entrepreneurship #public_policy #gig_economy #emerging_markets #economic_development #globalisation #economics #government